Skip this post if you don’t have any control issues.

Still here? Me too.

So let’s talk about control and the best way to publish your novel. So far, of the factors listed in Do You Need A Publisher (Part 1) that affect whether you pursue a traditional publishing deal or publish your fiction yourself, I’ve covered money and the desire for prestige or recognition.

Money is probably highest on my list right now because I’ve radically cut back my law practice, and my goal this year is to live on what I earn as a writer. (I have a long way to go, but that’s another post.)

If you’re planning to continue with your current career or profession, though, how much you earn from your writing might not be a driving force for you. As for recognition, for some writers, it’s the whole point. Others who have a first profession prefer to keep it separate from writing, so they use a pen name, particularly if they perceive their colleagues or clients may see their writing as a distraction.

Control, though, that’s another thing.

Who Needs Control?

Odds are, if you’re successful at what you’re doing now, it’s because you were able to manage your career well. If you run–or are a partner in–a business or firm, at the very least, you probably prefer choosing for yourself what you do with your time and how best to pursue your professional goals.

Also, and perhaps more important, most artists and writers want control of how their work goes out into the world. I once attended a horror convention where four novelists whose books had been made into films spoke on a panel. They agreed that helped them earn money, gain name recognition, and sell more books. Those of us in the audience wanted to know how they got those film deals and whether we could ever hope to get one. But three of four panelists spent most of the hour complaining about the hatchet jobs the filmmakers had done on their stories.

(F. Paul Wilson, the fourth panelist, declined to join the complaints. He said he hadn’t loved the film made of The Keep, but it prompted a lot of people who wouldn’t otherwise have found it to buy the novel, and that was all good. I really liked that about him.)

When it comes to control, traditional publishing is a bit like handing your fiction over to the film producer. I say “a bit” because you’ll have a say over revisions, unlike if your book were turned into a screenplay by someone else. The text of the novel is likely to be for the most part as you wrote it. You probably won’t, though, be able to choose which specific editor you want. And, as with a movie, as a new writer, you’ll have no control over how the final product looks, how it’s priced, or how it’s marketed.

How much does this matter? It depends.

Covers

At a writing retreat I attended, New York Times Bestselling Author Susan Wiggs showed slides of different covers one publisher had used for one of her novels. She wrote women’s and mainstream fiction. She had zero input into the first cover. It had a dark purple background, making the novel somewhat foreboding. It didn’t sell very well, despite her previous success and devoted audience. She pointed out over and over to the publisher that her readers reached for her books like they would reach for a box of candy.

Finally the book was re-released with an upbeat cover with pink edging that looked like ribbons. It did give the same impression as a beautiful box of Valentine’s candy. Her sales shot up accordingly.

As a self-published author, you choose your cover designer and your cover. Recently, despite that I loved the cover for my first thriller, The Awakening, I had it redesigned when a fellow author pointed out to me that it didn’t look good in the thumbnail size on Amazon. (I’ve pasted in both below—the original on the left, the new on the right.)

I also wanted the new cover to fit with the design for the fourth and final book in the series, which is coming out in May, 2017. Because I’m the one who chooses the design, I could make that switch without needing to convince anyone else.

Control has its downsides, though, because we don’t always have the knowledge we need.

I’ve seen indie authors choose covers that don’t convey the type of book or that don’t look professional. It’s also easy to get too wedded to your concept of the book without being a good judge of how that hits the reader. With traditional publishers, you’ll get a professionally-designed cover chosen by someone more objective who has more experience matching covers to genres.

Price

Have you ever gone on Amazon to buy a book thinking you’ll buy it for Kindle and start reading that day, then changed your mind and ordered a paperback when you compared the prices? Take Louise Penny’s latest mystery, for example, because I love her books so much. A Great Reckoning as I write this lists at $14.99 for the hardback, $14.99 for the ebook, and $9.99 for the trade paperback.

If this seems crazy to you given that ebooks don’t require printing or paper, you’re not alone. What’s the deal? Traditional publishers a while back won a drawn-out fight with Amazon so that they can price their ebooks as high as they want. It’s one of the reasons a slightly higher percentage of print books v. ebooks were sold last year than the previous year. If the ebook costs the same or more to buy, a lot of readers would rather have paper.

If you’re Louise Penny, author of a popular, long-running series, this pricing is probably fine. Fans like me will run out and get the book as soon as it comes out no matter the price.

For most other authors, though, this type of pricing is not so great. If I don’t know who an author is, even a compelling cover and intriguing blurb won’t make me plunk down $14.99 or even $9.99. I’ll put the book on my Goodreads shelf if a friend highly recommends it. But I’ll probably buy it only if I come across it again somehow and the price has dropped, I find it in the library or at a used bookstore, or I happened to get a nice check in the mail and I feel like spending.

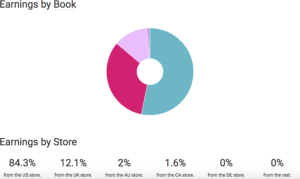

As a self-published author, most of my royalties come from ebook sales, then audiobook sales, then print. Because I get a larger share of the purchase price than do traditional authors, I can price my ebooks fairly low. In fact, right now, my first book in my series is free in all its ebook editions, then Books 2 and 3 are $3.99 and $4.99. At other times, I’ve priced The Awakening at anywhere from $4.99 down to $0.99—all much easier prices at which to entice a new reader.

Also, many of the email subscription newsletters that list bargain ebooks only list books at $4.99 or below. As a self-published author, I can choose to discount my book for the increase in sales or in the hope of selling later titles in my catalogue. Traditional publishers sometimes do the same, but the author has no say in when or how or why.

Marketing And Advertising

As an indie author, I pay for all advertising. Until this year, I wasn’t relying heavily on income from royalties, so I didn’t pay as much attention as I now wish I had to which ads result in the most sales. I know which ones were amazing—Bookbub and Ereadernews Today—and the ones that didn’t do much for sales, but for a lot in between I’m not sure. This year I’m experimenting cautiously and keeping better records.

Whether traditional publishers are better at knowing what works and doesn’t with advertising is an open question. But if you have a traditional publishing deal, the publisher is paying for the ads (and for premium placement in bookstores if you’re really lucky), not you, so at least you’re not directly bearing the cost.

Also, with a traditional deal, you can and should engage in marketing and public relations on your own. You can maintain your own email list, be active on social media, and contact bookstores about speaking there if your publisher isn’t doing enough for you. From what I hear, most small and medium-sized publishers expect authors to do quite a bit of that if they expect to sell.

Another sales issue is the summary on the book jacket or on line. As an indie, you write that book description yourself or engage a copywriter to do it. If you have a publishing contract, you give up that control. As with the cover, that can be good or bad. You may be able to do a great job writing your summary, and as an indie, you’ll be able to tweak the description to see what works. On the other hand, being a step removed, the traditonal publisher may do a better job targeting your market.

That latter point isn’t always the case, though. I’ve known several traditionally-published authors who felt their publishers missed the mark in how they described their novels.

Rights

What formats you make your novel available in is up to you if you self-publish. As I talked about in a previous post, as an indie author, I can make my books available as audiobooks, paperbacks, ebooks, and in any other format that comes along. I retain all my rights.

With a traditional publishing deal, often the publisher has those rights but is not required to use them. So you may give up your right to produce an audiobook of your novel, but the publisher may opt not to produce one even if you request it.

Righting The Ship

As in most other industries, it’s much harder for a large company to shift a business model than it is for one person. That’s part of why it’s taken so long for traditional publishers to begin marketing backlist titles as ebooks and to start email lists of their own when indie authors have used these tactics successfully for years.

That’s the main thing I like about publishing my own work. The books I’ve mapped out to write and publish this year may or may not be bestsellers, may or may not be popular, and may or may not earn as much as I hope they will. But if I’m not happy with my results, I can take different approach next year without any major upheaval.

So What’s Better?

As the pluses and minuses above show, there’s no one-size-fits-all answer here. Whether you’ll be happier having control over every aspect of your fiction or handing over much of it to a publisher depends on the pros and cons of the particular book, publisher, and deal. Also, it’s not an either/or situation. You can publish one novel or series yourself and seek a traditional publishing deal for another.

What will work best for you also depends upon who you are as a person. When I started my own law firm, despite that I had many of the same clients and did the same type of work as I had at a large firm, I enjoyed it much more because it was my firm. If I was working Sunday night, at least I was the one who’d chosen to take on that project or promised to meet that deadline. I also was the one who kept the profit. And, finally, down the road, I could adopt a different business model.

So far, I see writing similarly. If that changes as I move forward, I’ll let you know.

I hope this has helped you sort through your options.

Best wishes for a productive, not-too-stressful week.

L. M. Lilly

ned for, and filled with, readers. Step-by-step, Campbell-Scott walks you through how to use the social media platform.

ned for, and filled with, readers. Step-by-step, Campbell-Scott walks you through how to use the social media platform.

Good, bad, and indifferent, you need reviews of your first book. Once you have a decent cover and a solid book description, reviews are what convinces people who don’t know you to consider buying your novel. A large number of reviews shows a lot of people have bought the book, which cues readers it’s worth giving it a try.

Good, bad, and indifferent, you need reviews of your first book. Once you have a decent cover and a solid book description, reviews are what convinces people who don’t know you to consider buying your novel. A large number of reviews shows a lot of people have bought the book, which cues readers it’s worth giving it a try.